You completed your PhD in Medical Anthropology at UC Berkeley/UCSF working on issues of migration between Mexico and the US. Tell us about this research.

Vonk: I work with Central American migrants traveling through Mexico in order to document a border militarization pact called the Southern Border Program. Under the Program, the US quietly pays Mexico millions of dollars a year to detain and deport as many migrants as possible before they can reach the US and ask for asylum. The Program does this by physically immobilizing migrants—by taking away their means of transportation, or even by beating and maiming them—so they can no longer move. One of my main questions is: Is someone still a migrant if they can’t physically migrate? This isn’t just a metaphysical question. At stake is all of international asylum and refugee law, because if you can’t move, you can’t ask for asylum.

For this reason, I am also very interested in bodies, and what the migrant body is. I frequently work with people whose bodies “stick out” on the migrant trail, such as Afro-Latinx and trans migrants, in order to think about what it means to have a body that is seen as “different.” I also explore how documents like passports in many ways act as physical parts of our bodies—they grant us the ability to travel through the world. Without a passport, my body becomes physically stuck, it can’t cross borders. Some bodies can walk through walls, others can’t.

Thinking Through Borders

Thinking Through Borders

cademic and creative writer Levi Vonk joined the University of Virginia as a Global Studies Assistant Professor in Fall 2023 and is currently teaching courses on inequality in the media and global migration. He discussed his research, writing, and teaching.

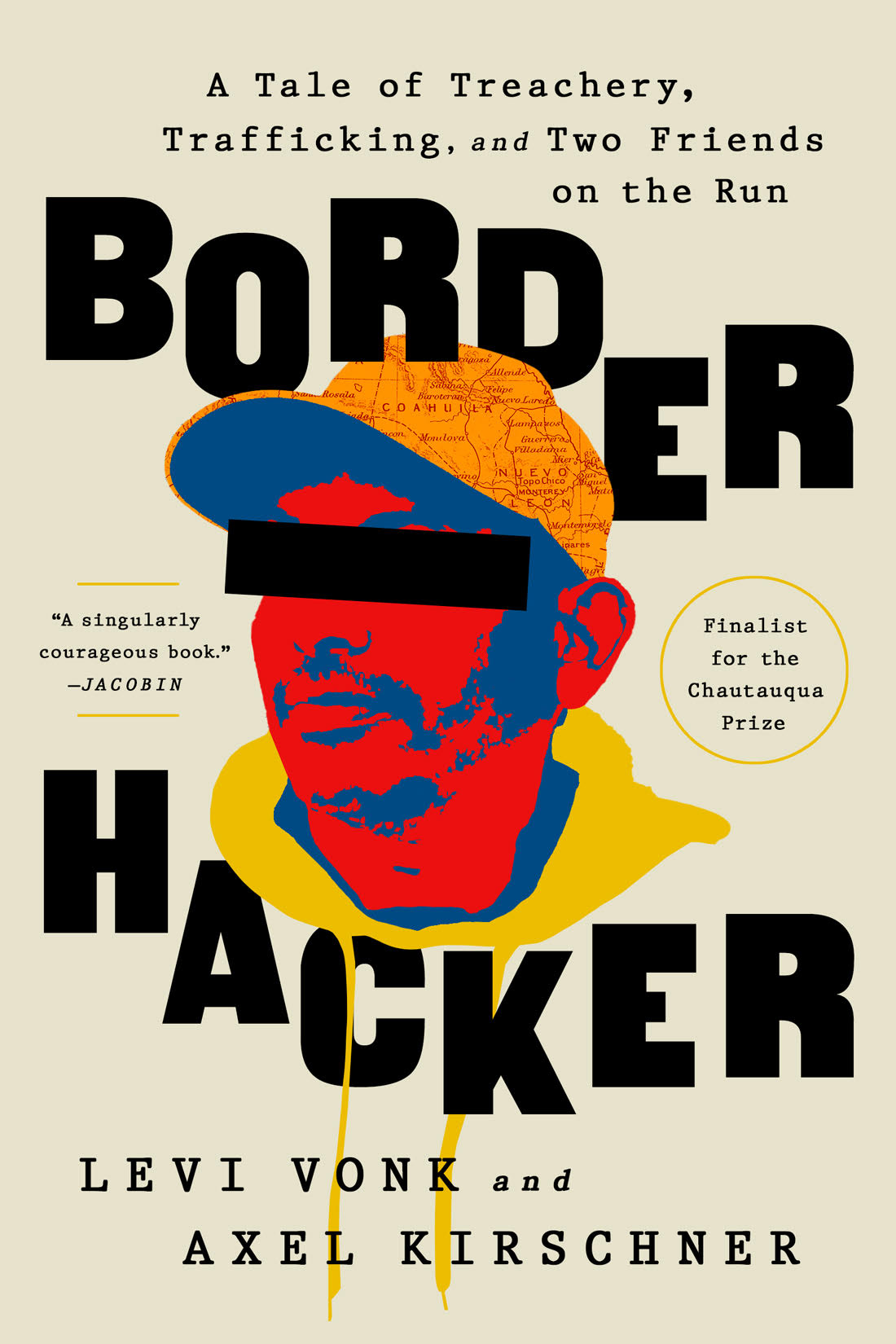

You’ve also recently published a creative nonfiction book, Border Hacker (2022). How does your creative writing influence your research, and vice versa?

Vonk: Border Hacker is an attempt to think about how to do creative nonfiction differently, and how academic research can be reworked to reach broad, public audiences. I co-authored Border Hacker with Axel Kirschner, an undocumented migrant and computer hacker, who was kidnapped in Mexico and forced to hack government officials. Portions of the book are authored in his first-person voice. The point was to give Axel space to speak for himself, even if he criticizes or contradicts my account of events. It’s an attempt to question the traditional subject-author divide in mainstream nonfiction while still telling a gripping and entertaining story. We also narrated the audiobook together, and we just sold the film rights to Hollywood.

I see this move—having multiple authors—as both very literary and very anthropological. Literary in the sense that it is invested in the beauty and creativity of Axel’s unique voice. As an Afro-Latino, undocumented migrant, Axel’s voice is not one that is usually given much space in literary nonfiction. The book is also anthropological in that it relies heavily on an intense ethnographic method—living and traveling with Axel and other migrants over the course of years.

I like moving between this border of mainstream and academic work. I grew up in a relatively poor community in rural Georgia, and whenever I’m writing, in the back of my mind I’m thinking, “Will the people I care about back home be able to read this? Will they get anything out of it?”

How does your work, both academic and non-academic, inform your teaching?

Vonk: My research is with vulnerable people who must live with the everyday consequences of concepts that might seem more abstract to UVA students, such as climate change, mass migration, undocumented status, and the like. My goal is to teach students that these events are not just happening “out there”—they are real things that our generations are called to face head on. In my classroom, we are not just reading for the sake of reading. I am trying to give students the tools necessary to face some of the most urgent problems of our time. I don’t want you to leave my classroom only feeling like you’ve learned something; I want you to leave knowing that you must do something.

At the same time, coming from a semi-journalistic background, I know the importance of telling a good story. And that’s how I view teaching: how do I take these important concepts and relate them to my students in a way that resonates with them, that contextualizes them in ways that they can apply to their own lives? That’s what keeps it interesting for me, and fun.

How will teaching in the Global Studies program change your approach to teaching?

Vonk: The Global Studies program is my ideal teaching environment because I have the freedom to both pull from multiple disciplines at once—anthropology, political economy, journalism, literature—as well as to pull from multiple societies across the world.

The Global Studies program therefore encourages starting with an international perspective, rather than understanding local issues as isolated from the rest of the world. I try to frame my teaching accordingly. I want students to think about how the issues they care about in their UVA communities are intimately and inherently tied to larger issues that everyone around the world faces, and to show them that there are people from a diverse set of backgrounds who have already thought brilliantly about how to best address these issues.

What courses are you offering this semester?

Vonk: I’m offering three courses this semester. The first is called “Journalism and Social Inequality,” which explores how the field of journalism identifies and frames social inequalities. My goal is to help students think about how this thing called “inequality” is presented to them in the media, and if there might be ways to think about inequality in a way that is both more complex and more effective in combating it.

The other two courses are on migration. One is called “Mass Migration and Global Development,” which explores mass migration’s relationship to social economic policy and global development initiatives. We will think about how migration is increasingly tied to economic and social policy, often in ways that are not always visible.

The last course is called “Migration and Social Movements in the Americas,” which provides an overview of migration and social movements in both South and North America, and it tries to better think through how migration is always an inherently political act. We’ll think about how many of the social movements that shaped the US today—from women demanding the right to vote, to the 40-hour work week—were led by immigrants, as well as other moments of migration that shaped the history of the Americas at large, such as the arrival of the conquistadors and the trans-Atlantic slave trade.